Introduction to Benedict Anderson

In one of Benedict Anderson’s most well known and well circulated texts, Imagined Communities he puts forth the following definition of the nation, in the context of nationalism: “it is an imagined political community – and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign (page 6).” The key concept here is the imagined community, which Anderson conceptualizes as a population of people who identify as being part of a nation but cannot possibly all know each other.

It is important to note as well his inclusion of the term limited. He uses this terminology because “even the largest of them, encompassing perhaps a billion living human beings, has finite, if elastic, boundaries, beyond which lie other nations. No nation imagines itself coterminous with mankind (page 7).” In this sense there lies an important concept of the ‘other’ or ‘outsider’ who are decidedly not part of the nation.

Following these basic principles Anderson argues that the basis for nationalism lies in the emergence of the following:

- Print & Print-Capitalism: Created a connectivity based on reading the same texts, publications and vernacular print despite not knowing others who speak the same fixed language there is solidarity.

- Communication and technology: The spread of ideas unified the mass public, this has only expanded since the days of publications as mass media – specifically Anderson points to radio as described in Exodus (page 321).

- Language and linguistic nationalism: The shift to vernacular speech in print allowed for the early 19th century European nations to subscribe to what Anderson describes in Western Nationalism and Eastern Nationalism as: “The underlying belief was that each true nation was marked off by its own peculiar language and literary culture, which together expressed that people’s historical genius (page 40).”

- Long distance nationalism: The idea that areas outside of ones state boundaries can be part of their nation, this is best examined by looking at Mary Rowlandson’s description of missing what she called England (in Massachusetts), page 60 of Long-Distance Nationalism by Benedict Anderson.

Through these concepts we can see that Anderson’s descriptions of the emergence of nationalism are based off of a core set of ideas that encompass a wide variety of intertwined topics, from capitalism to print to language. Our group has come up with three cases where we show the strengths and weaknesses of Anderson’s theory.

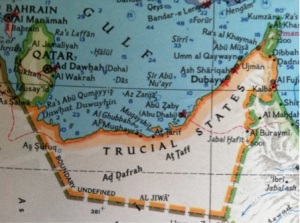

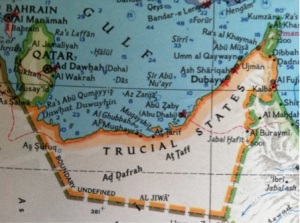

The Gulf as Imagined Communities

a) How is nationalism sustained where it has been created?

The Arab Gulf states could be applicable to Anderson’s theory of imagined communities and Gellner’s concept of creating a nation where it does not exist. These states flourished into being as a reaction the British colonial campaign. The Middle East was sliced amongst the European colonial states, and when it was time to turn to the Arab Gulf, the British had been too distraught from the war debts to delve into the process of full colonisation. Therefore, the states saw it as an opportunity to unite, there were multiple negotiations which included forging Bahrain and the Trucial states into one nation and also to include Qatar, but no result was ever satisfactory to suit all. Finally, it was decided the Trucial states would become the United Arab Emirates, while Bahrain and Qatar proceeded to declare their own states. Since these states don’t rely much on historical myths and pre-modern existence (the western definition of modern, since it could be argued that tangible modernity did not effectively begin in this region until the 20th century) it could be argued that the national narratives of an imagined community and the sheer necessity to maintain peace in a region that is continuously under threat is precisely how they sustain nationalism.

b) Threats against boundaries

To begin with, in order to establish the state, the threat of colonisation had already been recognised and reacted upon. The drive to unite the smaller units that had been previously installed by the British was imperative in order to declare a nation with a united front that could face the colonialists. Till today, the threat to its boundaries from the neighbouring Middle Eastern countries brings forth the need to maintain a nationality that is uniting and solidifying, not simply between a single state and its people, but even among the states and their people as well.

c) Political legitimation and emotional power

The threat to the boundary as Anderson has explained is when ethnic identities are brought to the forefront; it is when people become territorial and defensive of what they consider belongs to them. This in turn reminds them that they are to unify with those within their territory and exclude all those who aren’t, this emphasis allows the inclusion of some specific ethnicities and the exclusion of a lot many others that are considered too far off. The states political legitimation came from the same emphasis on ethnic identity that was also used to evoke emotional attachments among the people. Since the society is organised based on tribes, it was no struggle in deciding who the most powerful of them was and would retain power over the other less powerful tribes, thus appointing a government. The emotional power was evoked using the people’s tribal culture and values, emphasising on terms such as dignity, honour and pride of their ethnicity and lifestyle. It was a form of ‘official nationalism’ as Anderson describes, one that was initiated from a top down direction.

d) Religious aspect – nation as a sacred community

The shared religion among the people of the region made the task of unifying much easier. The sanctity of the state was derived from the same religious values that governed the people themselves, they could see their religious values being reflected and adopted by the state hence assigning it both legitimacy and respectability. As the religion of the state and its people coincided, the task of gaining allegiance and loyalty was achieved. Not only was the state accepted, it was looked upon as a sacred community, a community that was religiously unified. Thus the community began to value its unity and solidarity and it became a religious duty to accept and co-exist with one another, and to direct faithfulness, loyalty and to uphold the promise with the state to always be its citizen. A promise witnessed by God.

e) Other imaginings must erode – dynastic or religious communities

The decline of the Ottoman Empire in addition to the decaying history of the caliphates created a power vacuum in the region. With an impending British Colonialism, the tribes of the Arab Gulf were eager to avoid foreign control and colonisation. Nationalist sentiments of unity and state were appealing to the people, in as much as they helped defer foreign colonisation. The power vacuum was quickly diffused by tribal elites who were respected and celebrated by their peers. The feelings of hostility that were harboured against the dying empire and the impending British imperialism were sufficient enough to convince the people of joining a different more independent imagination that placed them in a reality that spoke to them more effectively.

Questions to think about:

- A nationalism that was carried out by the elites; who made them the elites of society when they were all tribes of either Bedouin or Coastal origins?

- How can a state create an ethnocentric history that concentrated on the people exclusively?

- How can it preserve this national narrative and imagined community in an area today considered one of the most politically unstable?

A porcelain rhinoceros and German Bratwurst

This month The British Museum inaugurated a new exhibition about German history. It’s title: “Germany: Memories of a Nation.” In order to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Germany’s reunification the exhibition presents a different perspective on German history, or better said, the many histories of what came to be Germany. The purpose is to show that Germany is more then those “twelve dark years,” as Neil McGregor, director of the British Museum, puts it.

Displaying a variety of objects the curators try to draw an impression on topics with which “every German can relate”. Covering a period of six hundred years the exhibition seeks to articulate the relation between the political history, characterized by a vast heterogeneity of states and a indeterminacy of borders; the on-going quest of Germanness, especially after the fall of the Holy Roman Empire and after the Napoleonic era; technological leadership and the idea of the highest accomplishments in production, invention and art; and finally the question: “how was it possible?” (Interview Director Museum on Deutsche Welle)

a) Political heterogeneity

The variety and homogeneity of states is visualized through the display of the different coins used in every state. And if we were to look at a historical map of the so called German territory the historic reality of the indeterminacy of borders becomes evident. The first attempt at unification after the decay of the Holy Roman Empire was the German Confederation (1815-1866), an association of 39 German states, including those parts of the Austrian Empire and Prussian Kingdom, which had belonged to the former Empire. It failed due to its heterogeneity and the on-going dispute over whether Prussia or Austria was the rightful ruler over the German territory.

b) The early quest for Germany

“Deutschland? Aber wo liege es? Ich weir das Land nicht zu fin den…” Germany? Where is it? I don’t know how to find this country… This quote of Goethe puts into words what the map with the coins depicts. The Napoleonic invasion was in some way a trigger for German nationalism. In a rather conservative attempt to maintain the status quo different groups start to define Germaneness, for example compiling songbooks of authentic German songs. Nonetheless the differences, especially the political heterogeneity, made it rather difficult.

c) Technological leadership

The porcelain rhinoceros, a copy from Albrecht Dürer’s famous print by the manufactory Meissner is just one example for technological innovation (production of porcelain). Another earlier example would be the Gutenberg Bible. A probably more known example around the world would be the VW Beetle.

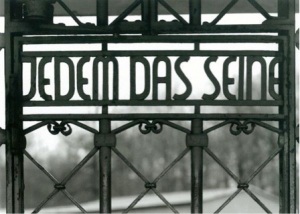

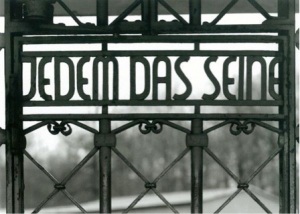

d) Weimarer triangle

The concentration camp Buchenwald was near the city Weimar. The same city in which Goethe lived and died and the place where the Bauhaus art college was founded by Walter Gropius. The picture shows the entrance of the camp designed by the prisoner Franz Ehrlich. For Neil McGregor this illustrates the question: how was it possible? And it probably also illustrates the awareness of history within Germany.

e) We are one people

With the reunification the quest of what Germaneness becomes unavoidable and forceful again. The task is to integrate the two different German experiences and perspectives to one general German idea. Beside this, the structural, political and economic integration of the two states has ben a big challenge. There are still differences, especially in terms of employment, population, etc.

f) Future oriented history

„ […] one of the ways that German history is not like other European histories is that Germans consciously use it as a warning to act differently in the future. As the historian Michael Stürmer says, ‘for a long time in Germany, history was what must not be allowed to happen again.’” The Reichstag, with his crystal dome, is one symbol for the future oriented perspective on political transparency. Combining a building loaded with historical memory and the democratic principal of transparency. The dome is open to visitors and grants a panoramic view to the city and at the same time the view over the parliament beneath it.

g) New patriotism

During the world cup in 2006 we could observe shift in the relationship with national symbols, especially the flag. The three colours were no longer banned from public spheres, though their presence and use is combined with humour. It reflects and encourages the process of leaving behind the omnipresent inherited guilt without neglecting the responsibility for the memory and the future.

h) German Bratwurst

German society is still characterized by its regional and cultural differences reflected in the dialects, customs, traditions and sausages.

i) Can we wrap it up?

What do you think about this exhibition, where German memories are gathered and displayed for a British spectator?

Do you think every German can identify with this imagery?

How does the idea of a territory defined by borders illustrated by maps and the creation of history and collective memory through museums and merchandise as instruments of structuring and categorizing a national memory and identity apply in this case?

Links

http://www.britishmuseum.org/whats_on/exhibitions/germany_memories_of_a_nation.aspx?utm_expid=1760025-3.htGHqpzSQG-BpO3BZXI8Qg.0&utm_referrer=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.britishmuseum.org%2F

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04dwbwz

http://www.dw.de/london-exhibition-aims-to-alter-germanys-image/a-17997670

http://www.dw.de/mad-about-germany/av-18006239

Case studies – Malaysia, Long-distance Nationalism

“Long-distance nationalism” is a concept introduced by Benedict Anderson in his book, The Spectre of Comparison: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World. Due to restless expansion of Capitalism, population mobility throughout the globe, involving studying and working overseas or even immigration, has become a commonplace phenomenon. Yet, as Anderson critically indicates, possessing passport of a certain country does not reveal anything about his sense of identity. When immigrants move into an unfamiliar society, in which they often cannot fully integrate, a sense of exile would possibly make them even more affiliated to their origin countries. Thanks to advancement of communication technology, they could easily follow the latest news or even directly get involved in current affairs of their homeland; in short, nationalism is no longer confined within boundaries of nation-states, especially in those multi-ethnic countries in which different communities has not been fully integrated or to some extent, segregated, such as Malaysia.

In Malaysia, there are various religious, cultural, and linguistic communities and many of them have close relations with different countries respectively due to historical and cultural linkage, especially Malay and Chinese (Chinese-Malaysian). Despite both ethnic groups embracing Malaysian national identity, they generally have different degree of attachments to Middle-east and China (or Greater China, referring to Mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong) respectively. Though some might argue that both of those attachments are not actually nationalist sentiment, as the former might be better categorized as religious community and the latter cultural community, it is still worth exploring the phenomena from the long-distance nationalism viewpoint because: 1) they share strikingly similar characteristics with long-distance nationalism; and 2) arguably, it does have some elements of nationalism, especially in the latter case.

Due to their strong belief of Islam, Malays generally prioritize their religious identity over national identity. Since Middle-East is always considered as the centre of Islam circle, Malays always concern about the region than any other part of the world and some of them even regard themselves and people in Middle-East as one community. As can be seen in the following link, after Israel’s attack over Palestine, thousands Malaysians, noticeably mostly Malay, staged demonstration on Malaysia’s Dataran Merdeka (Independent Square) and even boycotted Israeli products to show solidarity with Palestinian. With the rise of Islamic state, people who believe Malaysia as a moderate Muslim country will be astounded if they are aware that some extremists genuinely believe in the idea of Islamic state and even volunteer as Jihadists or comfort women in Middle-East. Though it is still confined within the small circle of extremists, it is undeniable that the ideology of Islamic-state is spreading among Malay community.

When it comes to Chinese-Malaysian, despite having fully recognized Malaysian national identity, many of them still have some sort of attachment, to different degrees, to China or Greater China, which is clearly demonstrated in the surprisingly heated controversy over Hong Kong Protest among Chinese-speaking circle. While the younger generation generally sympathize Hong Kong pro-democracy development, the older generation tend to support PRC as they believe the Greater China should be unified under the rule of CCP because it is in the process of realizing China’s “great rejuvenation”, which intriguingly, does give them a sense of pride based on the reason that they share the same root with Chinese. Therefore, the older generation’s sense of belonging towards China does not only include cultural identity, but also political recognition. (1) Can this complicated dual identity, which we have so often disregarded, also be considered as another kind of nationalism?

While Malays rarely saw Chinese in the pro-Palestine protest, Chinese could hardly find a Malay who concerns the development of Hong Kong protest; it shows that religious/ cultural/ nationalist sentiment actually plays dominant, or at least, significant part in the process. Yet, both communities instead insist on utilizing the slogan of “universal human rights” in the cases of Palestine and Hong Kong. (2) Does it illustrate the tension between (quasi-) long-distance nationalism and national identity in the sense that their loyalty to their own nation would be questioned if they did not even attempt to dilute their “unusually excessive” concern over another certain country?

Though advanced communication technology is apparently instrumental in fostering long-distance nationalism as Anderson proves, (3) can we argue that he neglects the power of religious/cultural linkage, which is arguably another important aspect, as illustrated by the foregoing cases? Another important question: (4) will long-distance nationalism or the similar religious/cultural sentiment play an increasingly important role with the advancement of communication technology? If so, how will it influence our world, which is predominantly defined by the concept of “nation-state”?

For Reference:

http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/thousands-attend-for-palestine-in-dataran-merdeka

http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/malaysian-women-join-middle-east-jihadists-as-comfort-women-reveals-intelli

http://en.visithainan.gov.cn/en/lynewsview_2289.htm

(Malaysian Teenagers Seek Roots in Hainan)

Read Full Post »

You must be logged in to post a comment.