Introduction and a general historical observation

Economic nationalism is, as Eric Helleiner argues, a term that can cover a wide variety of policies and actions. Form, not content, is the prime characteristic of economic nationalism; it can legitimize a wide variety of policies as long as these can be convincingly couched in national terms. Or, taking a less instrumentalist view, people can genuinely set out with the goal to find the economic policies that would, in their eyes, best serve the interest of what they imagine to be ‘the nation’. As last week’s blog already stated, such views are open for discussion; the national economic interests of the upper classes might be imagined very differently from those of the lower classes. Yet such conflicting views are arguably contained within nationalism itself. Often, opposing parties in such conflicts will equally try to present the nation as a bounded singular economic in which questions regarding redistribution and growth will eventually have to be grounded. Even individualist ideologies can stress that striving for one’s own enrichment is ultimately the best or only road towards economic growth in the national sense (e.g. the infamous ‘trickle-down economics’).

As a diffuse concept essentially based on form, economic nationalism has arguably been around since the advent of nationalism – regardless of the era in which we might place the origins of nationalist ideology. Yet in the same way that the character of nationalism has changed over time, so have the fundaments of economic systems (on all kinds of different scales) seen important changes. On can think of the introduction and changing importance of different resources (coal, gas, oil), and the perceived necessity to directly control lands that held such resources. In the same way, the view concerning the importance of land as an economic resource (for instance, in agricultural terms) vital to a healthy national economy, has seen a great shift, especially in the period after World War Two.

An interesting case concerning the use of agricultural land in nationalist rhetoric is that of Nazi-Germany. The concept of Lebensraum fed into the nationalist idea that ‘the nation’ would need space, not only in terms of ‘living’, but also in terms of agricultural lands to work on. The idea that working the land had some kind of spiritual importance for the nation is in part economic, for it implied that the wellbeing of the nation is derived from (having part of it) working in a specific economic sector. Working in non-industrialized and non-urbanized areas, these German pioneers would preserve a German ‘essence’ in the colonised countries of the East (C.C. Bryant, Prague in Black: Nazi Rule and Czech Nationalism, 2007). As such, the Nazi case provides an interesting example of the way in which the particular constitution of the national economy became an integral part of nationalist rhetoric. Equally, the defeat of Nazi-Germany and the end of territorial colonialism in the 1950s and 1960s created new conditions in which Western nation-states revaluated the merits of direct control over land in national economic terms. Amidst the postwar economic boom, the (old) European colonial powers soon found out that keeping colonies would not be economically viable in a national sense – for the metropoles were often unwilling to transfer resources from the ‘core country’ to the colonies – and that, breaking the pre-war imperial mind set, territorial colonialism was in the end not essential to the success of the national economy (Mark Mazower, Dark Continent, 1999).

Nazi propaganda: a booklet which dealt with the settlement of German colonists in the Eastern Territories. The motto reads: ‘with plough and sword to victory’

Questions:

1) In what sense have economic (r)evolutions in the course of the 19th and 20th century influenced the ideological content and associated policies of economic nationalism?

2) The Nazi argument for the promotion of agriculture in the German economic sphere is quite extreme; however, it might be legitimate to ask in what way the reliance of a nation-state on a specific economic niche could influence notions of national self-identity.

The case of Chinese economic nationalism

It is difficult to counter the claim that with the rise of China as a global power, we have witnessed an increase in bold and brash behavior from this new power: and why wouldn’t we? Its military strengths are expanding and its trade and economy are the lifeblood of numerous foreign states and corporations. Whilst millions of Chinese have been hauled out of poverty and in many places rich turned into super rich, numerous others in the West have been plunged into debt along with pay packets that have seemingly remained static. Further to this, we have often seen the shift of blame onto the Chinese. Without equal benefits once promised from economic interdependence being received everywhere, plus the need for politicians to pay attention to the demands of their own polity, the temptation of economic nationalism no doubt becomes even greater.

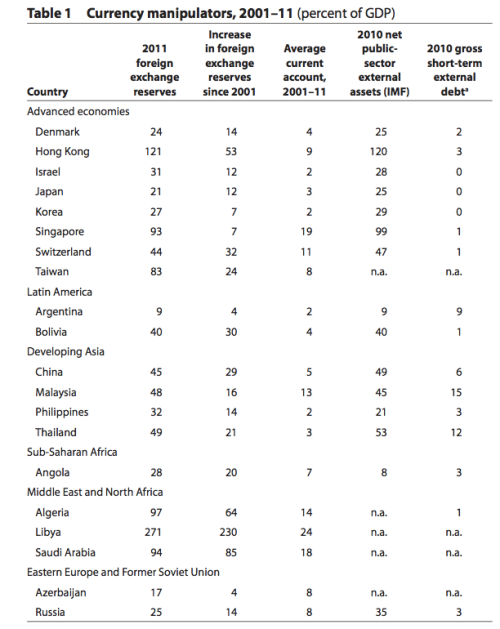

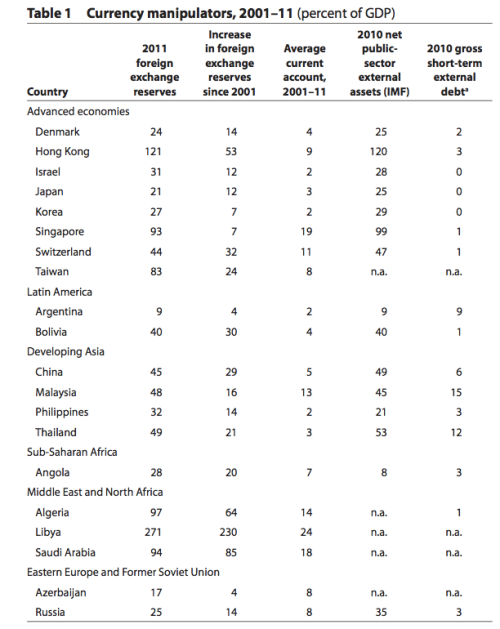

Recent global economic downturn witnessed political leaders gazing into the domestic realm for solutions to international economic and financial calamities, signaling the onset of currency wars. China’s financial behavior was highly politicized internationally, fanning the flames of Chinese indignation at the perceived handcuffing of its path to becoming a rising power. China has often been accused of currency manipulation, pegging their currency from 1995-2005, with brief periods reverting back to this after the RMB was de-pegged. Rhetoric painting China as a scapegoat reached a peak during the 2008 financial crisis, and even occurred as recent as the lead-up to the 2012 US elections.

Vital to note at this point in time, however, is that this argument is no longer valid. In previous years, such as 2000 and the aforementioned 2008, the label of China as a “currency manipulator” would have been worthy: not so much in 2012 as it is far from being the worst currency manipulator. China has made clear improvements in allowing their currency to appreciate considerably, whilst forgotten along the way are the role of other actors in manipulating the global currency system. Today it acts more than anything as an international insult, with potential for unwelcome repercussions given the at times pride-based foreign policy of the CCP.

The 12th Five Year Plan for China, in force from 2011-2015, confronts the raft of social problems facing China, such as the ever-increasing increasing wealth gap and rural/urban divide. This is to be done by implementing sustainable growth, industrial modernization and a push promoting domestic consumption, greening of the environment and a knowledge based economy. It is a FYP that suggests China recognizes its obligations to the international community and domestic population.

Counter-intuitive to this are the enduring disputes taking place in the East and South China Seas. Heads of state near and far are looking on anxiously, with some comparing the region to pre-World I Europe: “like the Balkans a century ago, riven by overlapping alliances, loyalties and hatreds, the strategic environment in East Asia is complex. At least six states or political entities are engaged in territorial disputes with China, three of which are close strategic partners of the United States” (Kevin Rudd).

The East China Sea has seen tussles between China, Japan and Taiwan over a small group of islands. The islands, known as Senkaku in Japanese and Diaoyu in Chinese, involve issues that run deeper than deep well oil supplies and economic gains; it harks back to Japan’s wartime and colonial period. The Japanese government bought the islands in September 2012 off private Japanese owners, which was seen as a blatant affront to the sovereign rights of China, and has thus caused a large realignment of military and naval personnel from both sides in the area.

In the South China Sea, there have been similarly tense stand-offs with neighbouring SE Asian nations. Clearly, the scramble for access to finite resources is ever increasing and China is keen to make a visible mark in the international relations arena.

Skirmishes and altercations have increasingly occurred, with the interdependence of economies amongst these tightly knit countries not enough an incentive to calm a progressively aggrieved tone of discourse evolving. Maritime standoffs, trade repercussions, public protests and fierce diplomatic rhetoric have all taken place. The Philippines is currently in the process of challenging China legally, under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which both parties have ratified, arguing China is claiming territory within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The problem here is, whilst any decision is binding, the tribunal facilitating the dispute has no enforcement mechanism.

On top of this, China recently commissioned passports showing the disputed islands in the South China Sea as Chinese territory. Separate pages in the newly issued e-passports include China’s so called “nine-dash” map of the sea, which protrudes hundreds of kilometres south from Hainan Island to Borneo’s equatorial waters. The nine-dash map, perhaps better than anything else, clearly paints a picture of China’s ambitions.

Effects of this have been far reaching: China has taken out full spread adverts in papers such as the New York Times arguing their case; a Chinese man in Beijing was beaten nearly to death for driving a Japanese made car; citizens from both countries have staged protests on the islands themselves whilst waving their respective national flags; restaurants have refused to serve Vietnamese, Filipinos, Japanese and dogs; boycotts against Japanese products have increased the speed toward Japanese financial meltdown and some Japanese firms temporarily shutting down operations during tense periods of protest.

Questions:

1) Japanese PM Shinzo Abe stated in a 2010 Washington speech, relating to tensions in the South and East China Seas: “In a nutshell, this very dangerous idea posits that borders and exclusive economic zones are determined by national power, and that as long as China’s economy continues to grow, its sphere of influence will continue to expand. Some might associate this with the German concept of “lebensraum.” Discuss.

2) Is China simply illustrating Shulman’s idea that China’s nationalist goals of “unity, identity and autonomy” are being fulfilled within the scope of liberal economics?

3) Is nationalism the evil or is it the structure of the liberal economic system?

4) Does Chinese economic nationalism exist or is it their opponents claiming the existence of it?

5) What role can economic nationalism play in a one party state?

6) Can Globalization be seen as having parallel themes to Marxism?

Nationalist and foreign takeovers

Economic nationalism does not just express itself in macro-economic policies. It also arguably appears in the way that certain industries or brands become emblematic of national identity. Thus, perceived threats to those brands, or to the national quality of those brands, can provoke a disproportionate reaction.

For example, the takeover of Cadburys by Kraft in 2010 was described by The Mirror as “the end of a British institution”. The great-great-granddaughter of the company’s founder was quoted as saying: “It appals me that a company like Kraft, that makes something you put on your hamburger, could end up owning Cadbury.” The Spectator said “it would be sad to see the British chocolate maker swallowed by a bloated US conglomerate .” Protesters outside the Cadbury plant in Bournville chanted “Keep Cadbury British”. In all these statements, there was a clear link drawn between the nature of the firm and the nationality of the owners: both Cadbury and Kraft were seen as having national characteristics that would bear on the way in which they did business.

(http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/krafts-cadbury-takeover-marks-the-end-195970)

In another example, rumours that PepsiCo was preparing a bid to takeover Danone provoked protests from French politicians, with Dominic de Villepin promising to “defend France’s interests” and calling Danone “a flower of our industry”. This opposition was tied to French government policy of creating and supporting ‘national business champions’, of which Danone had been one. The New York Times read this as politicians attempting to rally people round a national cause after the defeat of Paris’ 2012 Olympics bid and the failed referendum over the EU constitution. One commentator argued that American companies were seen as “soulless, only interested in making money, the very incarnation of worse aspects of globalization”, and claimed that the public would be friendlier to a takeover by a company like Nestlé.

(http://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/20/business/worldbusiness/20iht-danone.html?_r=0)

While protests in both cases did address concerns over workers’ rights, possible job losses and factory closures, and broader economic effects, much of the rhetoric focused on the firms’ identities as national brands. In this way, the workings of the market can come to be framed in nationalist terms.

Questions:

1. What role do brands play in national identity?

2. Are these really cases of nationalism, or are financial worries (e.g. potential job losses) the driving factor?

Read Full Post »

Off. Last year, a Muslim woman was crowned best baker. Some were pleased with this, stating that it forced viewers to

Off. Last year, a Muslim woman was crowned best baker. Some were pleased with this, stating that it forced viewers to

Trump? Fascism?

Posted in Comment, Nationalism in the News on November 18, 2016| Leave a Comment »

Many commentators – particularly on the left – are throwing accusations of ‘fascism’ at US President-elect Donald Trump.

In this measured and thoughtful blog Jane Caplan considers whether this is a useful analytical term ..

http://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/trump-and-fascism-a-view-from-the-past/

Read Full Post »